In 2008, the behavioural economist Richard Thaler and the legal scholar Cass Sunstein published a ground breaking book in which they advocated a novel approach to public policy based on the notion of a “behavioural nudge.

A “nudge” is an intervention in the decisional context that steers people’s decisions, actions, and behaviours by acting on their cognitive biases. The main point of their book is that people are often not the very best judges of what will serve their interests and that institutions, including government, can help people do better for themselves (and the rest of us) with small changes—nudges—in the structure of the choices people face.

Nudge theory is the science behind directing people to specific decisions and choices. It works on the principle that small actions can have a substantial impact on the way people behave. A recent follow-up book by Cass Sunstein called “How Change Happens” attempted to further explain how social change happens, the barriers to change and how to overcome them. Although there is a great debate about whether nudges allow people to go their own way and have autonomy, pre-selected options (known as defaults) are indeed commonly used as a law-making and public policy tool (e.g., having an employee be enrolled in a health insurance or pension plan). Just how well do nudges actually work?

Effectiveness of Nudges

There has been quite a bit or research on the overall effectiveness of nudges to shape and influence behaviour. However, a better question isn’t whether nudges work but for whom, under what circumstances, and to what extent do they lead to specific choices, actions, decisions, and actual behaviours.

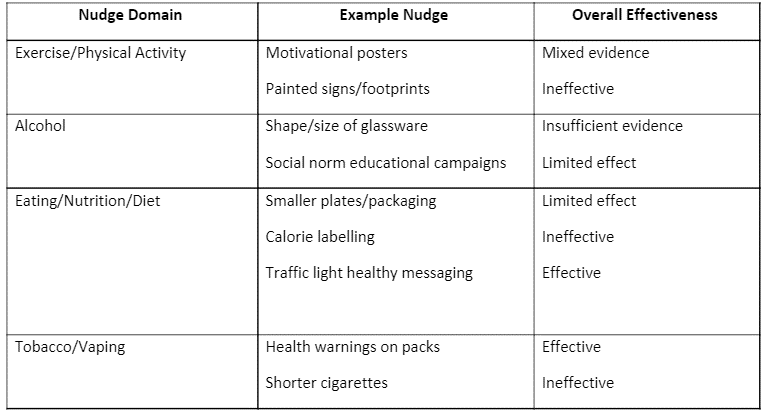

For example, Yiling Lin and colleagues from Queen Mary University of London have reviewed the effectiveness of nudges in four specific health areas including: 1) poor diet, 2) physical inactivity, 3) alcohol overconsumption and 4) tobacco use.

1Their conclusions can be summarised for each of these health domains below:

1. Lin, Y., Osman, M., & Ashcroft, R. (2017). Nudge: Concept, effectiveness, and ethics. Basic and Applied Social Psychology, 39(6), 293–306. https://doi.org/10.1080/01973533.2017.1356304

Health habits are particularly challenging to modify even when people are highly motivated to change and they utilize best practices in goal setting and reward strategies. The results of these researchers illustrate that even with nudges, getting started and moving forward to successfully change behaviours might not be quite as effective as we might want. It is also unknown in the health domain if nudges are more important to initiate goal setting or continuously once a person begins on their journey to sustain the desired behaviour over time. Given that complex behaviours to become habits take approximately 60 to 90 days, it would appear that nudges might need to be utilized for a longer period of time. What about evidence that extends beyond lifestyle behaviours?

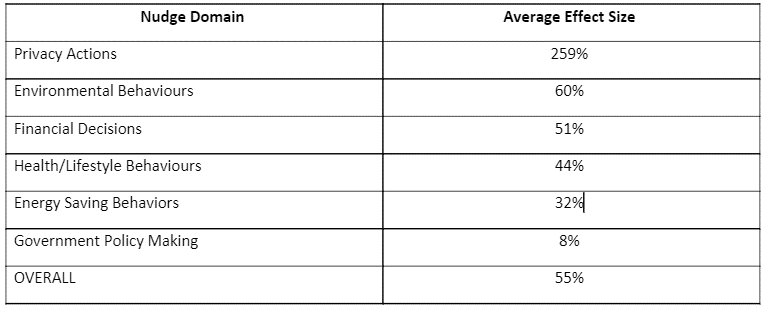

A recent review on the effectiveness (effect sizes) on 100 studies of nudging in different domains by Dennis Hummel and Alexander Maedche from the Karlsruhe Institute of Technology (KIT) in Germany also provides a way of measuring nudge effectiveness. They found that the median effect size for nudges in the domains of energy efficiency, environmental behaviour, financial decisions, personal lifestyle, health and well-being, policy making, and privacy actions was 21% (in general under 20% is considered a “small effect size”, 20% to 50% moderate, and higher than 50% is a large effect size).

Their findings indicated that the average effect size of nudges for six domains was as follows:

Overall, the effectiveness of nudges seems to not only depend on the nudge itself, but also on how it is perceived by an individual as well as personality and motivational factors. Most importantly, their analysis of the 100 studies revealed that only 62% of nudging treatments were statistically significant. Overall, nudges can selectively work for some people, in some domains, some time.

From Nudge to Budge

Whether governmental policies or individual behaviour change, it is important to consider nine of the most robust (non-coercive) influences on behaviour. The acronym for these nine is MINDSPACE and they were first described by The UK Cabinet Office commissioned the Institute for Government in a comprehensive report. Subsequent sections of the report discuss applying the MINDSPACE format in practice, the six main actions that need to be taken, public permission and personal responsibility, and future challenges:

Messenger (who communicates information)

Incentives (rewards and loss shape our behaviour)

Norms (we are influenced by what others do) Defaults (pre-set options or choices)

Salience (we tune into what is new, novel, and relevant to us)

Priming (sub-conscious cues can shape behaviour)

Affect (our emotions can shape our actions)

Commitments (we tend to follow up on our commitments to action)

Ego (we act and do things that enhance how we feel about ourselves)

Recently, a newer model about shaping behaviour beyond nudge theory was summarised by Oliver Hauer and his colleagues at the University of Exeter Business School in the U.K. These researchers suggest that the success of any intervention depends on understanding people’s current behaviour and their beliefs to make sure that any nudge will actually “budge” them from their current beliefs. Their new model extends nudge theory to what they call the BBC approach to systematically analyse what is driving desired behaviour:

B: Beliefs (what do people believe about the behaviour change, are they accurate, and would changing them have any real effect?)

B: Barriers (Are there barriers in the way of behaviour change and would removing or easing those barriers result in more successful effort and sustainment of new behaviour?)

C: Context (What is the physical and social setting and what is unique about the context for change and how does it shape the approach to a nudge?)

Budge

Successful behaviour change based on a clear understanding of a person’s current beliefs, barriers to change, and context or domain to be impacted

Identifies several mechanisms that impact successful behaviour change

Personalised nudges to maximise success

Can be tested experimentally

Hauser and his colleagues provide a set of examples and strong arguments on how to design a “budge” with the goal of identifying the psychology behind behaviour and understanding the psychology of the target population. These researchers argue that the BBC Model is a more comprehensive framework for applying the design of “nudges” and turning them into “budges” resulting in an effective shift in behaviours.

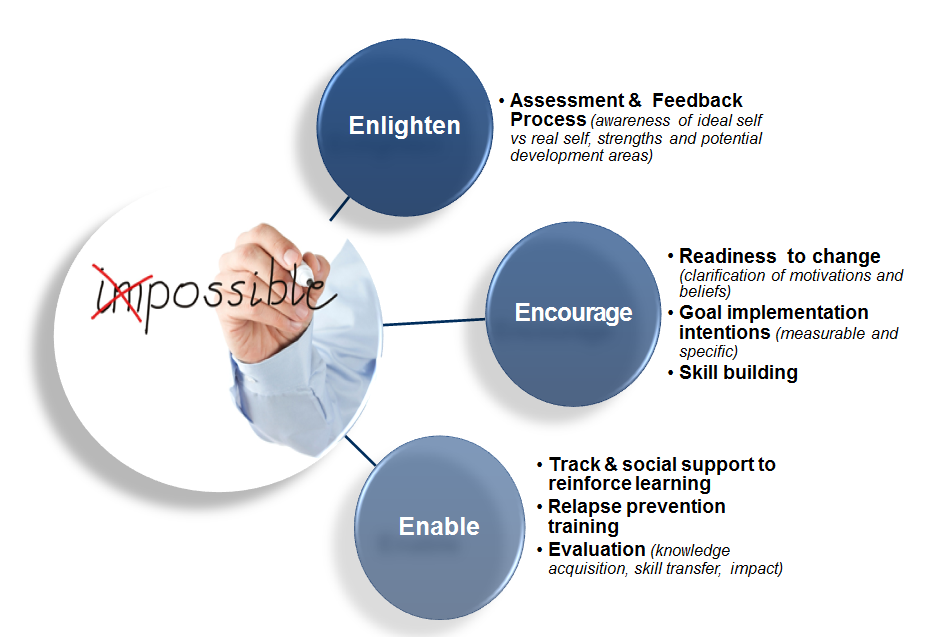

Finally, these researchers note that not all nudges will need to become “budges” but an opportunity for researchers and policymakers to truly analyse the issue or problem at hand and define what it might take to successfully change individual behaviour. Indeed, behaviour change is complicated and is influenced by a number of important factors that we have published previously. Our own 3Es model of behaviour change (Mashihi & Nowack, 2013) also provides a helpful framework for those doing coaching and training—we term these:

Enlighten (self-insight/awareness about the need to change)

Encourage(motivation and readiness to change as well as translating intentions into actions)

Enable (using social support, preparing for possible lapses, and measuring goal success)

Conclusion

Although evidence exists that nudging can work, there are a number of disappointing studies that support the idea that under some circumstances along with the right context and personalities of people they can be effective to shape behaviour. With modest effect sizes, and smaller effects on any goal that’s already highly valued perhaps using the BBC principles can help to improve the overall effectiveness of nudges towards actually budging people to make specific choices and take directed actions.

Kenneth M. Nowack, Ph.D. is a licensed psychologist and co-founder of Envisia Learning. Ken received his doctorate degree in Counseling Psychology from the University of California, Los Angeles and has published extensively in the areas of 360-degree feedback, assessment, health psychology, and behavioural medicine. Ken serves on Daniel Goleman’s Consortium for Research on Emotional Intelligence in Organizations and serves as Editor-in-Chief for the Consulting Psychology Journal: Practice & Research and is a Fellow of the American Psychological Association (Division 13; Society of Consulting Psychology).

How would you like to start a conversation? Click on the icons below, or use our interactive video tool.